Mills

Headley Mill

There is a reference to Headley Mill in the Woolmer Forest records of 978 A.D. The west end of the Mill is considered to be 16th Century and the centre is much older. In 1796 the bridge was rebuilt, and soon afterwards part of the house was rebuilt and the open water wheel covered in, major reconstructions took place to the fabric of the Mill and all the present water milling machinery was installed so that this contains a very modern layout as water mills go, the latest 'state of the art' in Stone flour milling machinery.

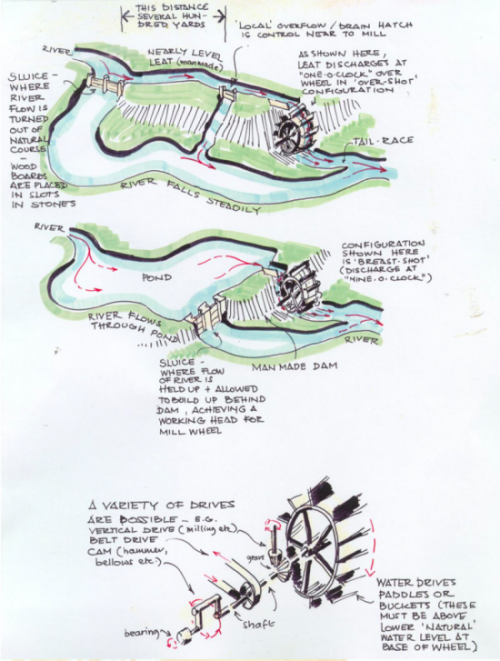

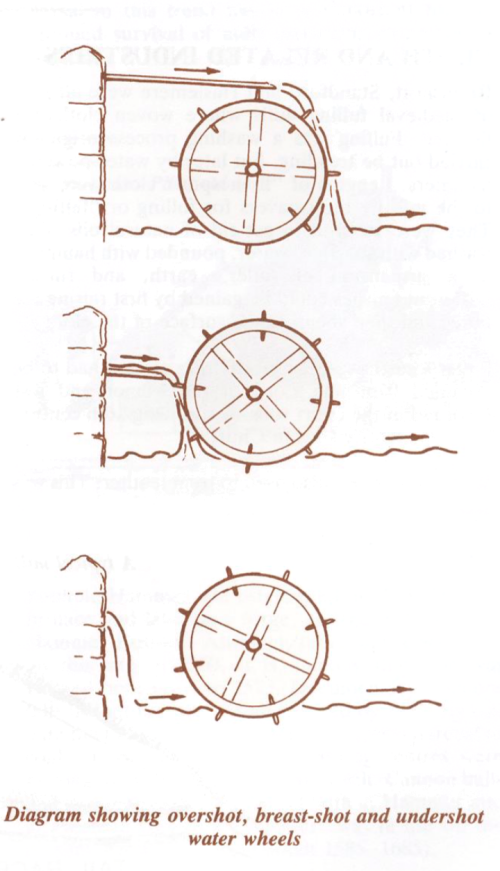

The Mill is built astride the river [the southern River Wey] facing S.E. with a pond of some 4 acres in front which provides the power to turn the breast shot Water Wheel (12 ft diameter x 7½ ft wide). The 'head,' which is the height between the pond level and the tail water, is approximately 7 ft. The flow is reliable and stable throughout all seasons, and is sufficient to drive a pair of Millstones perpetually.

The Iron Water Wheel was installed by Coopers of Romsey in 1926 when the old wooden one (oak and elm) was scrapped because of old age, but the shaft (iron) was reused for the new Wheel.

Power is transmitted to the Mill Stones and ancillary machinery by way of the Pit Wheel, which is an Iron Wheel (9ft in diameter) with wooden (oak) teeth, driving the Wallower (iron) which drives the perpendicular shaft on which the Great Spur Wheel (Iron 8½ ft diameter) is mounted. This is a very fine piece of early iron casting. The Great Spur engages the Stone Nuts (teeth of Beechwood) which drives the Mill Stones on the first floor where two bevel gears driven by the crown wheel drive auxiliary machines, crushers, rollers, electric generator, and Sack Hoist.

There are 4 pairs of Mill stones - 3 pairs French Burr (best for wheat flour) and 1 pair Derby Peak (oats & barley). The stones are 48 inches in diameter and weigh about 1¼ tons, and the dressing is '3 furrows to a harp'. The Water Wheel will drive 2 pairs of Millstones at a time.

The output of flour from a pair of Millstones with a good head of water is about 4 cwt. per hour, and Cattlefood about 6 cwt. per hour [1cwt = approx 50 Kg]. The fineness of the flour is decided by the Tentering lever which adjusts the gap between the 'Runner' and the bedstone. This can be done while the Millstone is running at full speed (120-150 rpm). The Wheat, after cleaning, is hoisted to the top of the Mill (Bin Floor) by hoist or elevator, and gravitates to the ground floor via the Millstones where it arrives as flour, and is conveyed to the centrifugals or dressers (by Armfields), and these machines decide the grade of flour i.e. 100% Wholemeal or 81% Plain Flour.

Maintenance: Gone are the days when professional Stone Dressers called regularly like the piano tuner, and mill owners now have to dress their own Millstones, fit their own bearings, shape new teeth, pack the necks, adjust the damsels, beat out the bosoms, and repair the skirts!